WASHINGTON: Congress hates base closures, known as BRAC. But it turns out you don’t need a Base Realignment And Closure round to hurt homestate economies. If you cut the Army by 120,000 (from a wartime peak of 570,000 to 450,000), and prohibit the Pentagon from closing bases, what you get — instead of wholesale shutdowns — is the death of a thousand cuts. Eventually, as the pressure builds, you probably end up with a BRAC anyway.

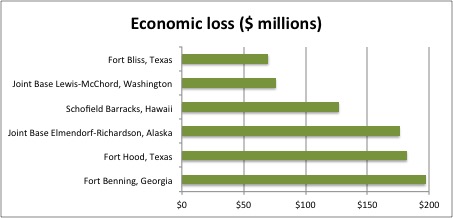

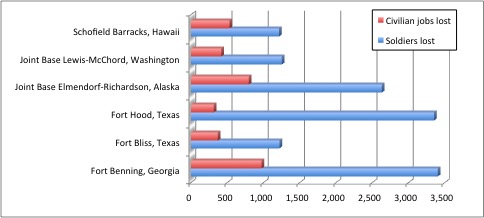

That’s the lesson our sources extract from the Army Secretary‘s official report to Congress on the most recent round of cuts, the 40,000-soldier reduction detailed in July. (The Federation of American Scientists just posted a FOIA’d copy online, but we got the report a few days ago and had time to pass it around to experts). Amidst the process details and boilerplate, the 22-page document enumerates some of the economic impacts of the cuts: an estimated $828 million in losses and 3,401 lost local jobs.

We say some of the consequences because the Army report is incomplete as it only coversthe six bases that were hardest hit, specifically the ones losing more than 1,000 servicemembers, the legal threshold requiring a report: Fort Benning, Ga..; Fort Bliss and Fort Hood, Texas; Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, Alaska; Joint Base Lewis-McCord, Wa.; and Schofield Barracks, Hawaii.

The report also only covers the immediate impact to private sector jobs near the base. It’s silent on federal contractors. It doesn’t specify how many federal civilian employees will lose their jobs, but with fewer uniformed servicemembers to support, the civil service will take a hit as well. “Information on the number of employees affected at the installations listed in this report is not yet finalized,” the report said, “but total Army-wide civilian reductions through FY19 are expected to be ~17,000.” (Yes, that’s 17 thousand).

In particular, a function called Base Operations Support must continue at its current levels while the troops are moving out, since managing the reductions is part of the BOS workload. Once the reductions in uniformed personnel are complete, BOS will go down as well. That implies some federal civilian and contractors who do BOS will lose their jobs.

Admittedly, contractors get hired for things like Base Operations Support largely because they can be hired and fired more easily than civil servants as workloads rise and fall. But that doesn’t make it less painful for the local economy — and local legislators — when they lose their jobs. “The whole reason why we outsource is so we can be a little more heartless,” said Michael O’Hanlon of the Brookings Institution. “On the other hand, for a local politician, they might not be comfortable with that logic.”

All told, the 3,401 lost jobs enumerated in this report are just the first of several shoes to drop. Local communities and their political representatives are bracing themselves.

“Congress can avoid a BRAC as long as it wants, but this outcome is worse. [It’s] a slow bleed,” said Mackenzie Eaglen, an American Enterprise Institute analyst and member of the Breaking Defense board of contributors. “The units affected and communities where it’s happening will tell you they’d actually rather have a base closure process than let the uncertainty linger and watch installations become shadows of their former selves.”

“The Army will be over 20 percent smaller when its endstrength cuts are completed in 2017,” Eaglen noted. “The loss of 120,000 soldiers in just over half a decade means that units, and some bases, are hollowing out from within.”

There are some silver linings, Eaglen went on. “The posts targeted for reductions over 1,000, however, are some of the Army’s biggest, so that will help with shock absorption,” she said. “It will also help other posts not feel like they are BRAC-bait by taking disproportionate reductions now and making them easier targets for the Pentagon when Congress does approve the next BRAC. (And it will. In about 3 years).”

The more the military shrinks, the harder it will be for Congress to justify keeping every base open, Eaglen argues. There’s already one subtle shift. The National Defense Authorization Act for 2016 — currently under veto threat — orders the Pentagon to study excess infrastructure, after years of banning even analytical work that might someday be used to justify BRAC.

“There is another provision in the bill that says the Department has to come to Congress with more specific data about where you think you have excess infrastructure,” said House Armed Services chairman Mac Thornberry yesterday. “What we’ve heard for the past several years is all based on a study they did in 2004,” he said — omitting the fact that Congress had forbidden such studies in more recent years — “and we’re saying, okay, let’s not just trot out old information over and over again. If you think you have too much infrastructure, come give us more specifics about it, and we’ll look at it, and there may well be another BRAC in the future.”

Between now and that hypothetical future BRAC — three years away, by Eaglen’s estimate — will the economic pain from these “slow bleed” cuts add up to enough to cause political action?

“I’m not sure it will actually change anything in Washington,” sighed Justin Johnson of the Heritage Foundation. “The congressional delegations affected by these cuts are largely already energized against defense cuts,” he said: Their votes are solidly in the “stopsequestration” camp.

“Because our large military bases and defense industry are limited to a relatively few states, I don’t think the economic consequences of defense cuts are enough to change the political situation,” he said. “However” — as the world gets worse from Ukraine to Syria to the South China Sea — “the geopolitical challenges are starting to have a political impact.”

In other words, if anything changes the debate on defense funding, it won’t be economic damage to home districts, but global dangers to national security. Sometimes all politics isn’t local after all.

Shared from Breaking Defense.